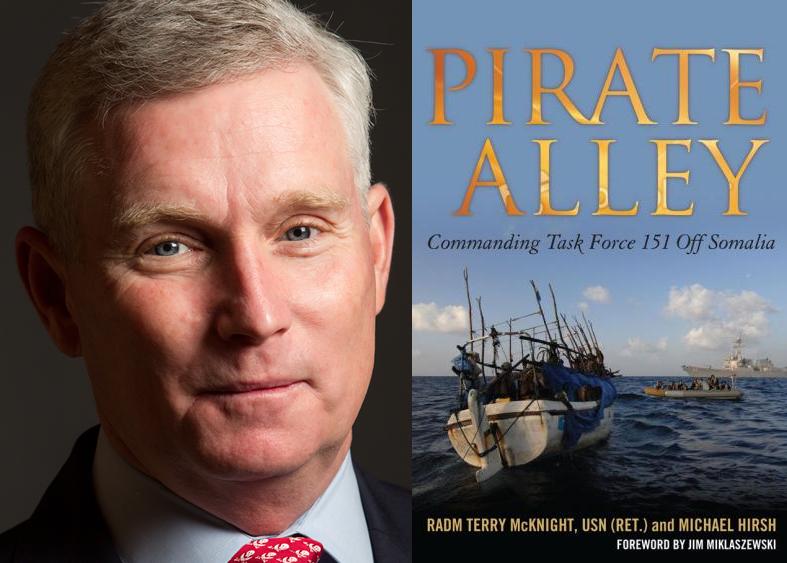

United States Navy Rear Admiral (Retired) Terrence E. McKnight commanded Task Force 151, which operated off the coast of Somalia. He recently authored the book “Pirate Alley” about his experience commanding an international coalition aimed at ridding the waters of ruthless Somali pirates.

He recently sat down with journalist Martin Edwin Anderson and discussed what he took away from his experiences in the Indian Ocean. Piracy remains an international problem in the Indian Ocean, and is also spreading to other areas such as West Africa and Southeast Asia.

In this interview, McKnight offers a recap of his task-force’s efforts, and his support for the international anti-piracy movement. Although piracy has been reduced, largely thanks the efforts of Task Force 151, McKnight remains adamant that the global naval presence should not be reduced.

McKnight also points out the significant role that private-security firms have played in the reduction of pirate incidents.

Andersen: One issue coming to the fore, given the increasing role of countries’ militaries in the fight, concerns how civil-military distinctions on water are claimed by some to have little parallel on land, and vice versa. Do you think that that is true and, if it is, what consequences has that brought to international efforts to fight piracy?

McKnight: When focusing on a land operation you have close scrutiny of what is going on. For example, we had security teams in Iraq and Afghanistan and you could see how they were operating day to day. The problem that I fear is that, when they are out on the ocean there is a fine line on the Law of the Sea and how these security forces are operating. Are they following the correct rules of engagement? Are they concerned about the well- being of mariners that are out there, such the problem of mistaking fishermen for pirates, and are they focused on the rights of the average citizen? So my biggest concern is the proper training on rules of engagement going after pirates.

Andersen: The unique cooperation among nations in Gulf of Aden has caused both positive and negative commentary. For example, China is one of the nations that is helping, but also carries with it human rights baggage from other arenas. How do you view these as potential lessons to be learned?

McKnight: I think that it is very positive that China is out there—it’s a good news story that they are out there and that they are working as part of a coalition. Every nation carries its own baggage; we all have our own problems. But I think we have to be cautious about what China’s goals are out there. Are they out there just to fight pirates, or are they out there to find how they can become a blue-water navy like we were in the early 1900s? We have to be very careful on how we deal with China.

Andersen: For example?

McKnight: If the U.S. Navy says maybe it can’t support anti-piracy operations, and now all of a sudden China says, “Well, we can be the leader out there,” putting a marker in the sand and taking over some of these operations. So we have to be very careful in how we deal with China.

Andersen: Following up on that, China is very involved on the continent of Africa.

McKnight: Absolutely right. They get a lot of their oil from there. If you look at the size of the Chinese merchant fleet—five of the top seven [world] commercial lines are Chinese flag vessels—so they have a concern. And the trade and goods from China are not only going to the U.S., they are going to Europe, they are going to Africa. So they have a keen interest that they have a free flow of commerce also.

Andersen: How can private companies help promote better standards and thus even better cooperation?

McKnight: I think you have to work with the militaries, to make sure that the private contractors are following the same standards as the militaries are following. Working together, training together. When I was in the Navy the biggest question was, is that person who is going to fire that 50-caliber gun on a U.S. ship trained and ready to go and knows how to respond? Do we have those same procedures in place? When you put a security team on a merchant vessel, how do they work with the master? Do they understand the language—is there a barrier? They have to understand those techniques so the master isn’t just throwing his hands up in the air and saying, “Okay, you just fire on anybody,” without concern for human rights.

Andersen: A number of analysts, looking at the progress that has been made in the Gulf and elsewhere, nonetheless warn about the increasing sophistication of some pirate organizations. Do you see evidence of that; if so where, and what might be done to anticipate their evolution?

McKnight: It’s a money-making business and they are going to try their hardest to stay ahead of us. When we stood up the task forces in the Gulf of Aden we pretty much knew that, once we stood them up, they were going to try to go out into the Indian Ocean. That’s exactly what they did. How did they extend themselves? They took mother ships. So they are always looking for tactics to overcome those of ours. And they are like anybody else— they are going to hire consultants, and they are going to say: “How can we defeat armed security teams? How can we get better?” We didn’t think that some of them would operate at night, but now we’ve seen operations at night. If they want to continue to make money off of piracy, they will change their tactics.

Andersen: In your book you suggest that the successful protection of targets such as container ships and crude oil carriers may result in pirates turning to crime on land, such as the kidnapping of foreigners. Have you seen examples of this, and if so, where?

McKnight: What we are seeing is a lot of sailboats coming out of the Seychelles [an island country spanning an archipelago of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean], or coming out of the Maldives [another group of islands in the Indian Ocean], that are high-risk, high-interest targets because they are very easy to hijack. The sailboats aren’t worth anything, human property is, so what they are going to do is capture these people, take them to land, and ransom them. We have a couple of cases where people have spent a long time in Somalia because of the high ransom payments. And who can pay these ransoms? The governments are not going to pay them, so it’s up to the families to get the money to get these people out of captivity. Right now we are seeing it in ones and twos, but that isn’t to say that it couldn’t happen later because in the spring time a lot of these sailboats are trying to get through the Gulf of Aden into the Mediterranean before the trade winds change, so you see a lot, a lot of sailboats in the February/March time frame.

Andersen: In Latin America one of the problems with the drug traffickers is the so-called “balloon effect,” where when you come down on criminals in one area, they just establish operations in another country or another subregion. Is this also a danger in terms of the pirates?

McKnight: We thought we had the problem contained in the Gulf of Aden and then it went out into the Indian Ocean, and then it went into the region of the Seychelles. So they are going to go out there and do what it takes to hijack some of these vessels. We’ve seen them out 1,500, almost 2,000 miles, along the coast of India. If they can get the vessels and extend their reach, they’ll get out there.

Andersen: Looking back, what do you think are the lessons concerning the best ways to outfit ships for travel through high-risk areas?

McKnight: It is very surprising, and very inexpensive, but the No. 1 thing is lookouts. If you have a keen eye, if you can see what is going to happen—whether it is on a radar, or a visual lookout—it is perfect. A lot of these commercial ships didn’t have lookouts. We are only talking about a 450-mile journey to go through the transit lanes. During that time period you want to be on your highest alert.

The other is speed. We have never seen a merchant vessel going over 18 knots that has ever been hijacked. It is too complicated for them. Speed, look outs, simple things like fire hoses over the side; listening to the warnings that come out from the UKMTO [UK Maritime Trade Operations] office—all those things help tell where the pirates are. It is a matter of being vigilant and ready to go.

Andersen: In one sense, those facing piracy in the Gulf of Aden particularly, and in and around the Indian Ocean, were fortunate in that pirates there were demanding ransoms, which many consider “newsworthy,” while those problems involving things like maritime armed robberies appear to get much less attention. What more do you think needs to be done to raise international interest in a problem that is clearly on the rise in other parts of the world?

McKnight: One of the issues is paying the ransom payments. Merchant communities will tell you that they have to pay those ransom payments or else they will not get mariners to transit those corridors. If we continue to pay those ransoms, there will continue to be acts of hijacking and piracy. We have to reach a resolution that says, ‘Okay, we are not going to pay ransom, and we are going to protect the ships going through those areas so that they do not get hijacked.‘

Andersen: Clearly U.S. policy has changed over the last several, particularly regarding Washington’s position on the role of private security firms. Now that some claim the threat of piracy is on the wane in the Gulf, what changes, if any, do you see for private firms, including their role vis-à-vis multinational and national government maritime security efforts?

McKnight: One thing I hope does not happen is that, because piracy is on the wane, navies don’t start to pull out. If navies start to pull out I think you will see private security teams that will not be as protective and you will see piracy start to pick up again. It is private security firms, the navies, and the maritime community, working together, that can bring down the number of piracies.

Andersen: It would seem that, given the fact that the maritime industry is hurting worldwide (due in large part to the rising cost of insurance and the escalating costs associated with capture by pirates), some of what is underscored is the importance and the factors involved with pricing of possible solutions. How do you think the market is handling those, and what—if anything—more needs to be done?

McKnight: I think you’ve seen a little bit higher prices in markets. If the insurance rate goes up, the customer is going to pay for it. If you have a transit journey that is extended to avoid pirate areas the customer is going to pay that. Let’s say that if piracy does pick up, and merchant vessels decide to avoid the Gulf of Aden, you could see a spike in the oil prices in the United States.

Andersen: One problem continues to be a question of international law and how the status of private armed patrol boats remains unclear. What do you think is being done to effectively address those problems and what more needs to be done?

McKnight: One thing is that the United States has to sign the Law of the Sea Treaty. As the leader of the world and of the maritime community, we have to get onboard with everybody else. The United States fears that we have a UN tribunal, that sort of thing, but if the navies cannot provide protection for shipping, and we have these private security teams, how are we going to enforce the Law of the Sea, just like we enforce the laws of any nation-state; how do we enforce it in the Gulf of Aden or on the Indian Ocean?

Andersen: What are the possibilities for additional practical coordination between public and private forces against piracy?

McKnight: One of the key events that we have is the Shared Awareness and Deconflation (SHADE) conference [hosted by the 26 partner nations of the Combined Maritime Forces], where we get together with all the coalition navies, which could be a good mechanism to bring the merchant and private security communities together—so we’re all in the same room talking about the same thing. We could talk about our needs, and share intelligence. If the U.S. navy knows that there is a pirate cell operating in Somalia, we need to share that information with the private security teams. It is not a national security thing; it is a law enforcement issue. We don’t have to share how we got the information, we just need to identify where the threat is, if they need to avoid that area, or—if we know that there is a mother ship operating in a certain location—to make sure that every vessel operating in the area is on the lookout for possible pirate activity.

Andersen: Those working in private sector solutions maintain that highly-professional guards lower, rather than exacerbate possibilities of violence and therefore fundamentally reinforce human rights and other legal considerations. How important is this in the context of today’s threats, and why?

McKnight: Most of the security teams are hiring ex-Special Forces members who are trained not only on selfdefense, but security issues. All indications are that the majority of the teams that are out there are sanctioned by the governments and have gone through some type of certification, on how they are trained and what they are trained for. So it’s not like the Wild West, where it was: “Let’s just form a posse and grab people off the street.” The last thing you want to do is have a company that is sending people out there who are not trained and we have an incident that would put a bad name on the maritime community.

Andersen: There has been a lot of talk that this is such a small slice of the pie of global commerce, so is it cost effective to send multi-million-dollar warships out just there to fight the pirates?

McKnight: I think it is. I think that every nation that is out there has a concern for the free flow of commerce around the world. In 2012 and beyond, the world is going to get flatter; it is not just the European Union or another group that are the only ones trading. For the U.S. Navy, one of our key missions is the free flow of commerce. With piracy, if we don’t have enough ships we have to figure how to have the right assets out there to protect that free flow. Admiral (Michael) Mullen, when he was chief of naval operations, talked about the 1,000-ship navy and everybody in Congress thought, “Oh my God, we can’t afford a thousand ships.” What he was talking about was all these navies, the 1,000 ships were all these coalitions working together to protect commerce wherever it is. We just don’t have the resources alone, ships are more expensive; we have to operate at extended ranges. The more we work together and cooperate as coalition forces, the better off we are going to be.